Surp Stepanos Church

Surp Stepanos Church, prior to 1915, photograph colorized and restored in 2017

Surp Stepanos appears to have been the principle church in the village.

The church, located in eastern Efkere, is built on sloping ground, overlooking a brook, and overlooking Eastern Efkere. It was built and re-built numerous times, with the first known mention of it from a manuscript dated 1683 from Simeon the Scribe.

The current structure, which remains partially standing, dates from 1871. Alboyajian, in 1937, described this as “a magnificent, bright, cross-shaped church with high arches, with a beautiful bell-house and dome.”

The reason for the rebuild in 1871 is unknown. There was a huge earthquake in the Kayseri region in 1835, which did cause damage to the monastery in the village. Did it also damage Surp Stepanos? While this is not documented, it would seem likely.

The architect is unknown, although interior decorative elements do bear a striking resemblance to those of St. Mary’s Armenian Church in Istanbul (Surp Asdvadzadzin in Besiktas), which was built by Garabed Amira Balian in 1838. The semi-dome decorated with a multi-cross pattern, the four paintings in elliptical frames in the pendentives (of Sts. Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John), and the form of the inner decorative columns are very similar between the two churches, and examining St. Mary’s gives one a sense of the beauty that must have existed with Surp Stepanos.

Fortunately, there are some surviving photographs of this church that date from before 1915.

It is also unknown with certainty whether the current building was built on the same site as the previous church with the same name, although this would likely be the case. The cornerstone, located at the northwest corner of the building, does have a fairly lengthy inscription, and appears to be older than the surrounding stone. Unfortunately, the inscription has become quite worn over the years, and is now difficult to interpret. It is conceivable that this is from the previous church of the same name, although further investigation is needed.

Surp Stepanos is a cross-shaped church that is set on a hill overlooking the river that runs through the center of the village. It is laid out in an east-west orientation. The land drops off sharply approximately forty feet in front of the church, resulting in a clear view of the building from Western Efkere.

Smooth cut stone measuring approximately 30 x 60 cm was used in construction. These stones are interconnected with poured metal bracings, which are not visible from the outside or inside of the building.

Fugen Ilter carried out some architectural studies of the church, and did provide some general external dimensions for the church in 1982 [“Darsiyak ve Evkere–Kayseri’de XIX, Yuzyildan Iki Kilise”, Anatolia-Anadolu (Festschrift Akurgal) XXII, Ankara, 1982]. The church measures 25.5 m in length, and is 15.3 m in width. The small northern and southern wings extend out 1.65 m. The eastern (rear) wing measures 3.35m and the western (front) wing is 7.45 m. The gabled roof has an opening 11.9 m in diameter, where the dome once rested.

Fortunately, more detailed studies of this church are being carried out by Seyda Güngör Açikgöz, which will add greatly to our knowledge of this building.

The interior of the building is remarkable in several respects. The apse is laid out in a semi-circle. It is covered with a hemi-dome, which is adorned with a beautiful multi-cross pattern. This can be seen clearly in the photograph of Surp Stepanos to the left, which dates from approximately 1913.

The entrance hall of the church, conversely, is laid out rectilinearly, and is covered with a vaulted ceiling.

Unfortunately, the dome is no longer present, and has been missing since at least 1919.

Stunning drone photography of Surp Stepanos Church and the surrounding countryside, 2022, by Evrim Gür

Carved Stone inside Surp Stepanos Church, 2022. Difficult to translate, but the first line reads: “Dear God Have Mercy” and, further down, perhaps, it reads “Svajoghli Khoja”. Photo courtesy inanç Firat Erdogan.

A small building, which is currently used as a home, is attached to the south side of the church. The purpose of this building is unclear. Boys and girls schools were located adjacent to the church prior to the First World War, but in an interview that I conducted with a former resident of the village, these were thought to be on the northern side of the building.

The bell tower, once just south of the church, is no longer present.

Above, drone photograph of Surp Stepanos church, approximately 2019. Photo courtesy Evrim Gür

There are no longer any buildings adjacent to the church on its northern side, although some foundations remain.

By 1919, the dome and altar would be gone. Still, the structure remains standing to this day.

Because the structure is built into the hillside, the height of the structure from the back (east) is only a little more than 8 feet. It is therefore possible to climb onto the structure to where the dome once was, and see into the church from above. This view is shown in the video below.

The front of the building, by contrast, has a height of over 80 feet.

Surp Stepanos Armenian Church in Efkere, 1998

In 2002, as part of her doctoral thesis, Şeyda Güngör Açıkgöz carried out an intensive architectural analysis of the church. I am grateful that she has allowed me to present some of her work here: (click on images to enlarge)

Surp Stepanos Church, January, 2022. Video footage above provided by inanç Firat Erdogan.

Surp Stepanos Church, Interior, June, 2023

East side of church, site of former altar.

West side of church.

Congregants would enter from the west side of the church. The stone wall seen clearly in the first photograph is a relatively new addition—added when the church was used as a private residence long after the building had been used as a church.

Southern wall of church:

Northern Wall

Interestingly, approximately 10 feet above the floor level, there is a brick in the wall that is inscribed in Armenian, and is set upside down. It was clearly covered in thick plaster, and the fact that it is upside down only adds to the mystery. This is clearly seen in the third and fourth photographs below. In the fifth photograph, I have inverted the image so that the text is correctly oriented.

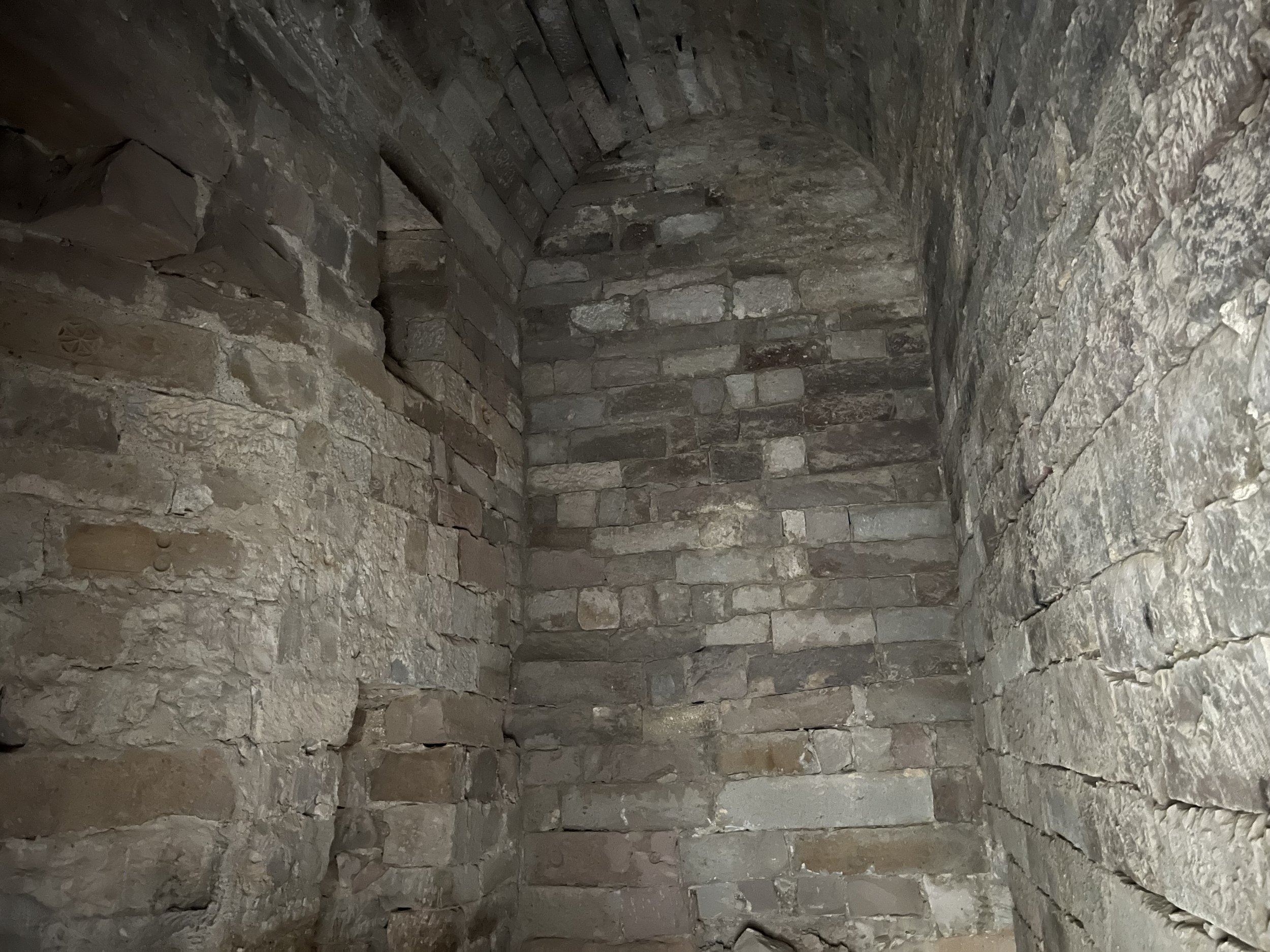

Behind the altar

Behind the altar, there is a passageway leading to some small rooms. Likely, this is where the priest and deacons prepared prior to the mass. Vestments may have been stored here. There are some interesting carvings on the walls, which are shown below.

As mentioned previously, much of the church was rebuilt in the 1860s, likely owing, at least in part, to the devastating earthquake that shook the Kayseri region in the 1830s. However, because the church is built into the side of a steep hill, this entire area is below ground. One wonders if this area of the church dates from well before the rebuild of the 1860s.

The first photograph below shows the entrance to this area, which is almost directly behind the the eastern-most point behind the altar.

Surp Stepanos Armenian Church in Efkere/Gesi Bahceli, Kayseri, Turkey—the Room Behind the Altar

Surp Stepanos Church – The Cornerstone

The cornerstone for Surp Stepanos is located at the northwest corner of the building, just above ground level. Here are photographs of it, with different lighting, in the hopes that somebody may be able to translate it.

It is difficult at this point to determine if the stone is from the most recent construction of the church in 1871, or if it is from an earlier date. Any assistance in translating the stone would be greatly appreciated.

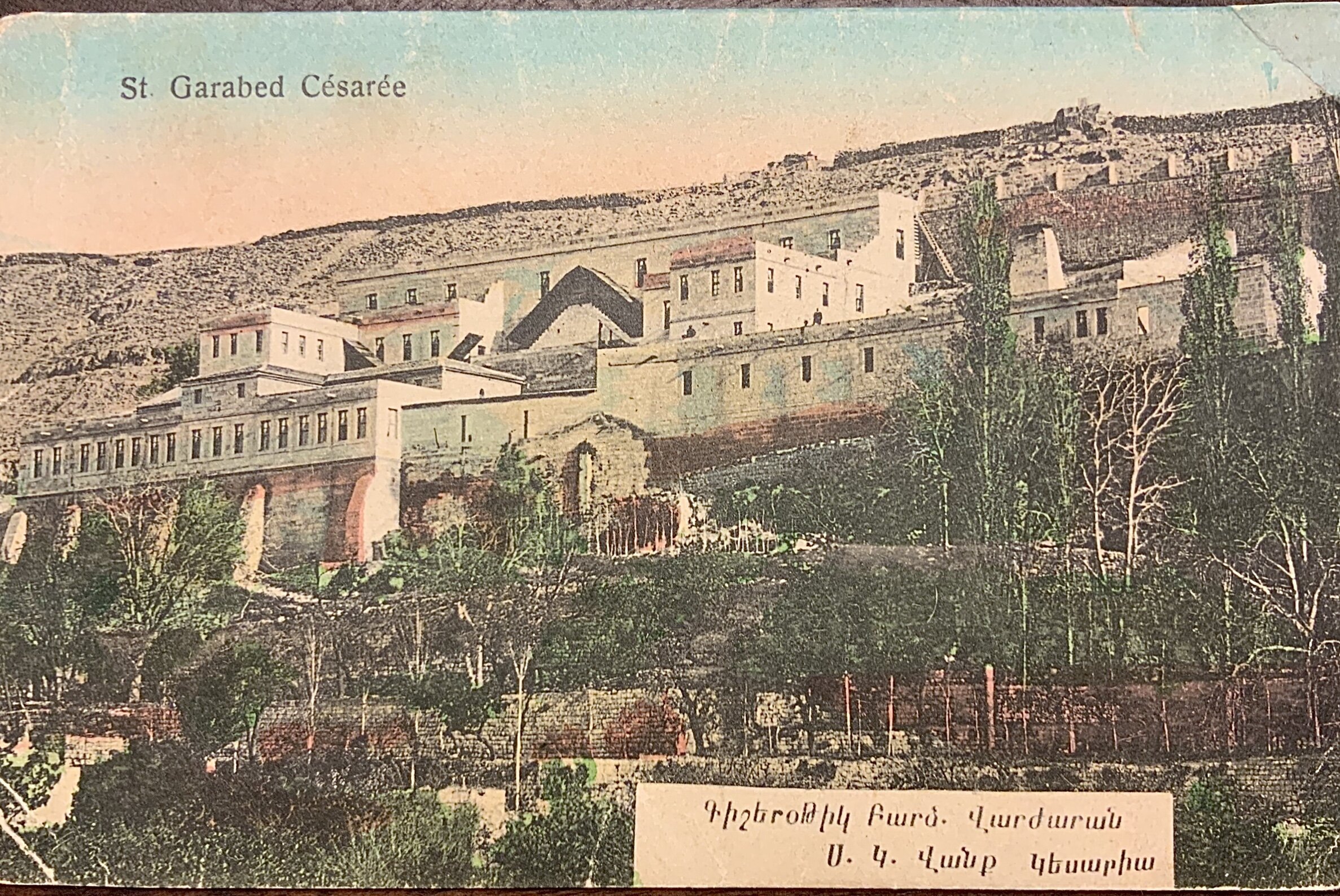

Surp Garabed Vank

The sprawling Surp Garabed Vank (St. John the Baptist Monastery), resting high on its hill in Western Efkere. 1897

At one point, Surp Garabed Monastery (or Vank, in Armenian) in Efkere was one of the most important sites of pilgrimage for Armenians throughout the Ottoman Empire.

Robert Hewson (Armenia: A Historical Atlas, 2001) describes it as having been “one of the wealthiest, most frequented, and most sacred shrines of the Armenian Church.”

It should be noted that there were two Surp Garabed Monasteries in the Ottoman Empire of extreme importance to Armenians, the other being near Muş.

Known in Turkish as Efkere Buyuk Manastir, the Armenians named the monastery after St. John the Baptist, whose relics were said to be housed here. Legend holds that St. John the Evangelist located the remains of St. John the Baptist in Jerusalem, and sent these relics to Ephesus. The relics were relocated to Caesarea in 251, and in 301, St. Gregory the Illuminator appealed for them. St. Gregory was said to have received a portion of the relics (the bones of the left arm and of both legs), and carried these relics with him as he traveled from Caesarea to Armenia. Resting at the site that would become the monastery, it is said that he raised a large cross on the hillside, and left a portion of these remains in Efkere. The hillside where the monastery is located is known as Surp Khatch, or Holy Cross, in reference to St. Gregory’s raising of the cross here. Another portion of these same relics are said to be at the monastery with the same name near Mus.

The exact date of origin of Efkere’s Surp Garabed Vank is unknown, however, and some locals believed that it was St. Thadeus who established it it in the first century, rather than St. Gregory the Illuminator in the fourth century.

The first clear reference to the monastery is from an Armenian colophon dated 1206.

By the time Simeon Lehatsi visited the monastery in 1617-1618, Surp Garabed Vank was clearly a large, and impressive center:

“St. Garabed, which was on the high hill, with a dome, large and glorious, the whole city lying before it. And there is a vast and expansive field before the monastery. And all the buildings and villages are Armenian, and all the churches and monasteries are built and completed…And it is quite an amazing building…”

Perhaps Yeghiazarian provides the most thorough, and evocative, image of the monastery. This passage of Yeghiazarian’s was quoted by Alboyajian in 1937:

You enter, your heart palpitating in veneration, through its low, wide, and thick door, and ascend a staircase in a semi-dark passage, the floor of which is made of polished black rock. When you come out into the light, another door appears to your left—towards the north. As soon as you walk through it you see a long and narrow passage, similarly semi-dark. To its left, on the rampart, the apartments of the monks can be seen, lined up in a long row. And, on the right, once again hidden in semi-darkness, you see a door, which opens into what seems to be a long passageway and into a cupola, which is the external vestibule of the monastery’s shrine. A mysterious spirit has possessed you there—the darkness and the moldy scent of humidity, mixed with the aroma of incense and candles, and, finally, the lifeless but more than alive creatures (the paintings with their eloquent expressions) seem to have subjected you to a magnetism of sorts. They look at you with questioning glances; some smile, and their smile has a celestial nobility; some scowl, and their scowls awaken memories of sins within you that you wouldn’t want to admit even to yourself; others are sad—that sorrow reminds you that you are a slave to, or afflicted by, moral grief and you are consoled by the holy sorrow reflected on the face of the saint on the wall. And it is in these thoughts that you remember that all your forefathers before you had knelt on the moist anvils of this vestibule and in front of these walls, perpetually wet by the steam of humidity. And automatically, you kneel, too, the final link in your ancestors chain. If you weren’t a believer, you are now. And even if you never prayed before in your life, bits of prayers spring out from a corner of your mind—prayers that you learned, albeit by force, in your childhood. When you stand up, you feel that life is easier—its grief is less tragic and its desires are hardly worth anything. Then, you go in through another door. You see a shrine, perpetually dark and mysterious. It’s three small altars, placed sided to side, are kept in the mystery of the darkness, as if it is the ample shadow of the believer’s God that has covered it. It’s four thick, cubical columns, its walls decorated with valuable porcelain, the domeless arches hanging over your head—on one hand they bear upon you like a grave sin and, on the other hand, they inspire a dream of eternal infinity within you. The prayers and hymns, which monks would sing take on a different meaning—they are more profound, and closer to the gods. Maybe that is why they are pronounced so softly there.

A door can be seen on the left, as well. You enter. You are in a second shrine, a smaller one. Ahead of you lies yet another door, a door fit for fairies this time, made wholly of mother-of-pearl—this is the most valuable jewel of St. Garabed’s monastery, and the talisman of Turkoarmenianism. Beyond that door, writhing the chapel-like altar, in a grandiose tomb of marble, rest the remains of St. Garabed, which were gifted to Gregory the Illuminator by the Catholicos Ghevontios, and, as it is said, brought by the former’s own hands to this grave.

At the end of the corridor, both floors above which the residences of the monks are lined, another door is visible. It opens to the school of the monastery, which is wonderfully located. First of all, a wide courtyard opens in front of you, with shining stones as a floor. The expansive hall of the academy rises further up, with its interconnected divisions—twelve classrooms, an observatory, a studio, and a guestroom—all of the bathed in Nature’s abundant light. Most of their windows look out to the fortress, Khas-Bakhcha and the other-worldly view beyond it. The other windows open out to the courtyard surrounding the academy on all four sides. A winding staircase can be seen in the right corner—it leads to the houses, where the teachers reside, two paved promenades, the refectory, the kitchen, and, finally three bedrooms, located quite high.

Coming to the southern half of the monastery, its vast courtyard is lined on three sides with special rooms for pilgrims, divided into lanes—Sarmisakli lane, Tokat lane, Nor lane, Kayseri lane, Çesme lane, and Zeytin lane. The rooms on the right side, with the arched promenade in front of them, look out directly to the valley. The double-rowed rooms on the left side, with their backs to the mountain, look out to the courtyard and, beyond the tops of the rooms on the right, to the expansive view. The stables for carriage horses and the water cisterns are located below the right and left lanes, respectively.

Besides all this, the monastery has its own cellar, a few perennial springs, a granary carved into stone and, finally, its nunnery—albeit constantly unoccupied.

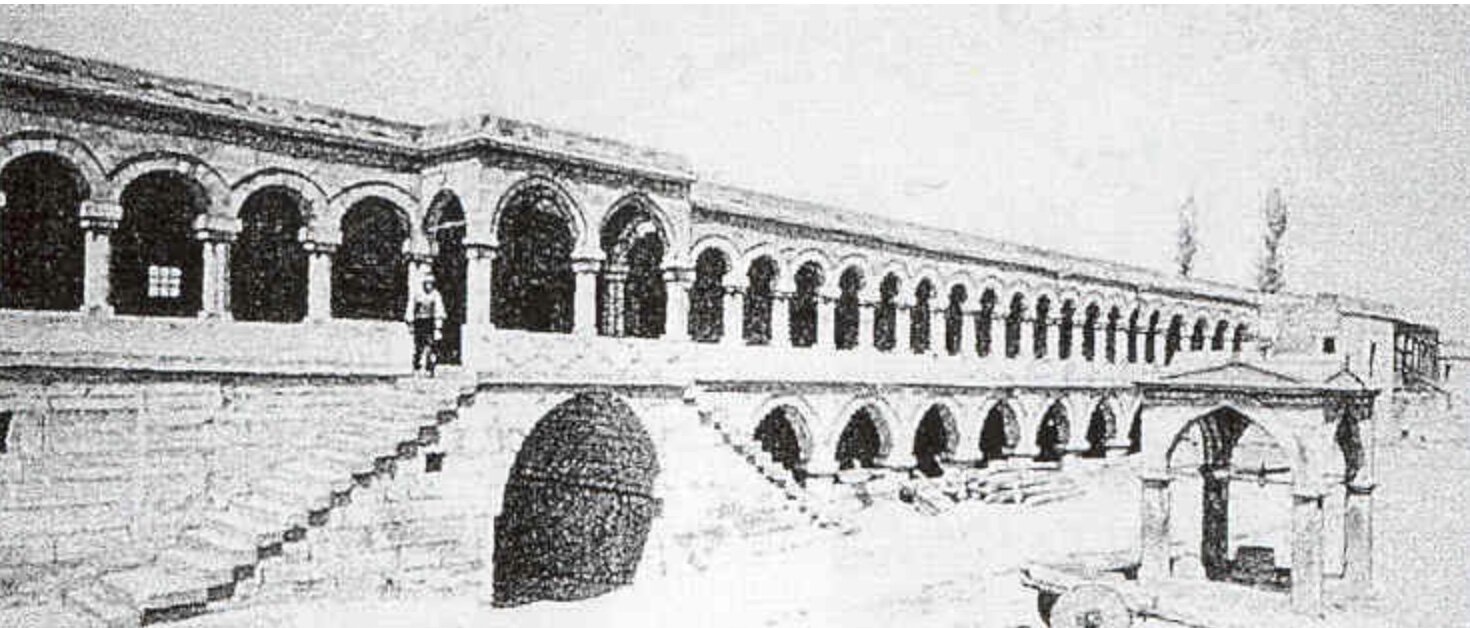

Reverend H.F. Tozer traveled to this part of Anatolia in the late nineteenth century, and his description of Surp Garabed Vank is included in his narrative, Turkish Armenia (Longmans Green and Co., London, 1881): The gate of the entrance stands in the middle of the front, where a long terrace overlooks the steep slopes below. Here we found the monks and a number of the other occupants of the monastery waiting to welcome us, for one of our zaptiehs had ridden on and given notice of our coming. By them we were conducted to the guest chamber, a good-sized room with a divan running around three sides of it, and a large airy window occupying the whole of the front, and commanding a superb view…In Armenia we heard it spoken of as ranking probably third among the conventual establishments of the Armenian Church, those of Etchmiadzin in Russian Armenia and of Jerusalem being the two first…

After the moon rose, the appearance of the plain below our windows, with the long shadows of the poplars thrown over it, was very impressive. During the night, we heard the noise of the semantron, a wooden board, grasped in the middle by the left hand, and repeatedly struck with a mallet – by which here, as in the Greek Church, the brethren are summoned to prayers; and again, at an early hour of the morning, the sound of chanting proceeded from the church, boys voices being distinctly audible among the others.

Per Alboyajian: “The grave of Saint Garabed was located near the northern wall of chapel. It had a very beautiful marble gravestone, which you could reach by the three stairs. On the grave, a very beautiful, completely gilded and wooden baldachin was built, which was decorated with different sculpted ornaments and gilded pictures, and was standing on 4 columns. Probably, the chapel of Saint Garabed’s grave was the oldest building in the monastery.”

The mother of pearl doors leading into the chapel where the relics of St Garabed were housed.

The monastery had many revisions and additions carried out over the centuries, and became a sprawling complex by the time of the First World War. The northern half of the complex included a school building with houses for teachers, dormitories, a kitchen, and a library with an extensive manuscript collection. The southern half of the complex included a barn, a very large courtyard surrounded on three sides by walls, and 93 rooms for pilgrims.

Per Alboyajian: As one entered the monastery from the side, a few steps up were climbed, which led into an open area. From here, one could enter the church of the Holy Archangel. This beautiful sanctuary had its walls covered with tiles from Kutahya, extending 3 feet above the ground. Above these tiles, two rows of paintings, all framed in gilt, lined the walls.

A chapel of even more importance within the monastery was Surp Garabed Church, which was the older of the two sanctuaries. This was the site of the crypt which contained the relics of St. John the Baptist. Two doors heavily inlaid with mother of pearl led into the crypt.

The monastery was generally open to the villagers daily for prayer.

Two photographs from the collection of Krikor Garabed Koltukian (1892-1968), and kindly used with the family’s permission. While the exact location of the photographs is unknown, the fact that Koltukian spent his early years in Efkere leads me to believe that these are indeed photographs of Efkere. The first photo (left) shows what appear to be the side of the monastery. The photograph on the right is a bit more difficult to identify, but certainly could represent an inner courtyard of the monastery. To learn more about Krikor Garabed Koltukian, consider reading this collection of his artwork

In addition, the expansive grounds in front of the monastery were also an important social gathering place for Armenians from Efkere, as well as from much of the surrounding area. Aleksan Krikorian, a native of Fenesse, Turkey, related the significance that the monastery had to Armenians from his village, which was some forty miles from Efkere:

“Soorp Garabed Monastery in Efkereh was…a venerated holy place for the natives of Evereg-Fenesse. The pilgrimage to this sanctuary was organized in connection with the Transfiguration. Armenian pilgrims in large numbers traveled there from all over to pray, rejoice and spend a pleasant holiday. The rooms of the monastery were made available to the guests…People made donations to the monastery and paid for ‘madagh,’ each according to his means. Those having made vows or pledges also brought gifts, such as silver items. ‘Madagh,’ the Divine Liturgy, and various services were held. Candles were lit on the grave of Soorp Garabed and lame, blind and crippled persons, as well as those suffering from other afflictions, would kiss the ground, hoping for miraculous cures. Those women, who bore children only after participating in a pilgrimage to Soorp Garabed Monastery, took their children there and ‘bought’ them from the saint in order not to remain indebted to him…After the Divine Liturgy, a feast was prepared and the monastery confines looked like a fairground.”³²

Yeghiazarian describes the monastic complex as follows:

The sight of its arched promenade, its amphitheater-like streets, and especially the school constructed recently fills your heart with frolic. And when you are near it, you notice its centuries-old rampart, on top of which, like eagles’ nests, the rooms of pilgrims as well as the apartments of the monks and the abbot are lined up – you are already charmed…To appreciate [the monastery’s setting] to its attractive fullest, one has to go up the rampart’s arched promenade. An almost circular field stretches out in front of you, wrapped in the beautiful season in a wonderful greenery; in the hot season, in the harvest of the monastery and the nearby villages; and, in the winter, in a monotonous sheet of snow, which is barely interrupted by footprints and irregular tracks…On the left, at the corner formed by the adjacent hills that are to the south, steep cliffs, with a road climbing through them like a staircase, though which cheerful pilgrims pass and turn, or a few paths, through which the monastery’s goats wander…

Recent Photos of Surp Garabed Monastery

Surp Garabed Vank interior, date unknown, 1940s?

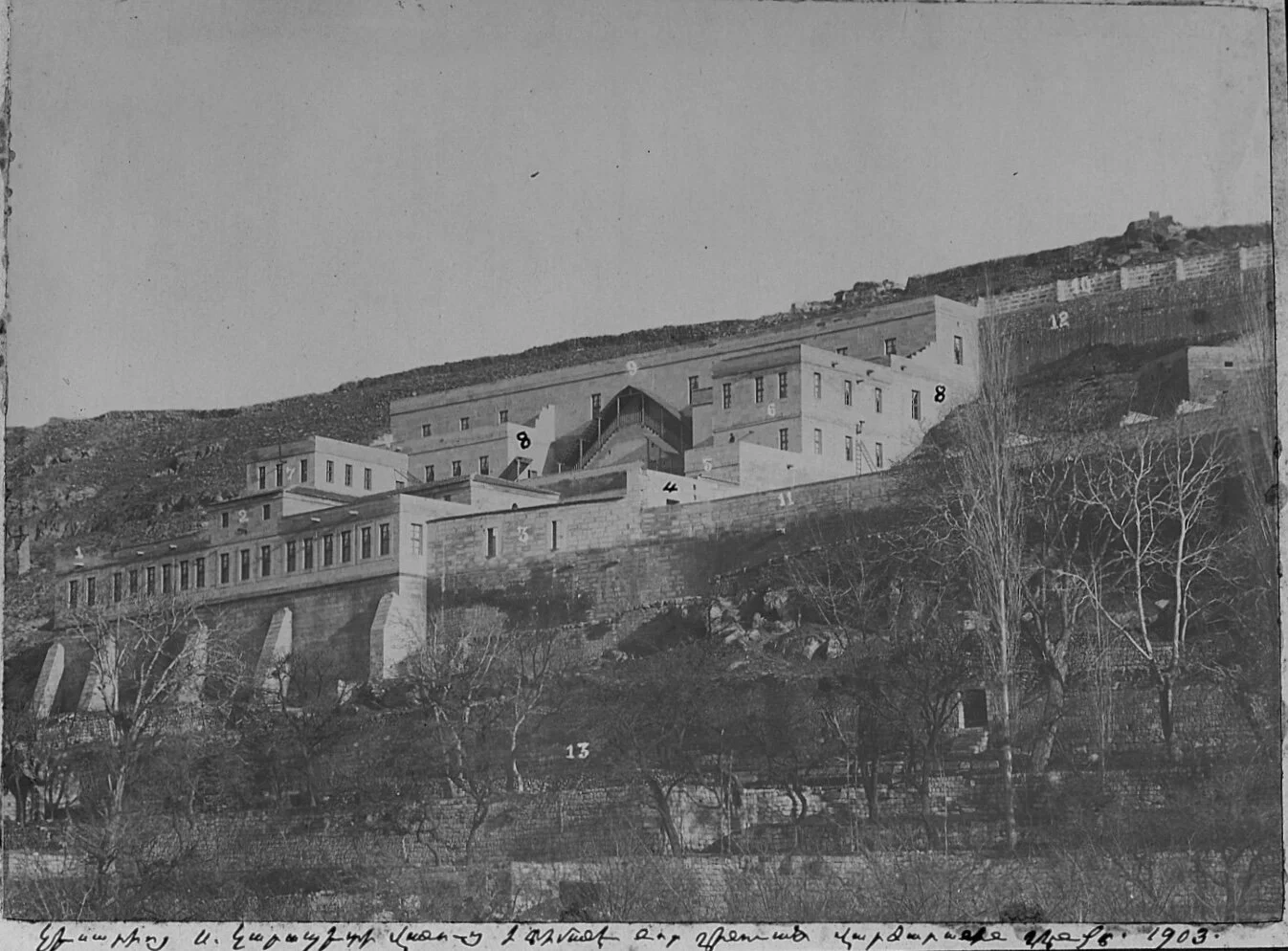

The ruins of Surp Garabed Monastery, 2003.

Armenians from all over Anatolia made pilgrimages to this monastery. During the summer months, many families from the surrounding villages, and from Kayseri, stayed on the monastery grounds. 93 rooms were available for pilgrims, which on feast days could number in the thousands.

Surp Garabed also served as an important center for education, with a school being built on monastery grounds prior to 1750.

Bishop Dertad Balian became primate of Kayseri in 1887, and created a high school at the monastery shortly afterwards. The school was opened in May, 1888 with 16 students. This school existed until 1915, and had a total of 215 graduates, some of whom are included in the photos below.

Bishop Dertad Balian

Graduating Students

The following list of graduates of Surp Garabed Vank is taken from Arshak Alboyadjian’s book, Badmootiun Hye Gesaria. I am indebted to Denis Der Sarkisian of France for kindly translating most of these names.

Also included next to many of the names of the students is the village or town that they were from. Note that “Gesaria” is the Armenian term for Kayseri. Some brief notes made by Alboyajian in the 1930s are also included.

Alboyajian noted that “Hmayag Oughourlian and Garabed Aprahamian have carried out a study in the 1928 Almanac of the National Hospital (pgs 221-262) entitled St. Garabed’s Monastery and College of Gesaria and Bishop Drtad Balian, where they have published a list of graduates (pgs 254-259), which I have used. But I find it necessary to mention that having been compiled based on memory, it is full of mistakes. Using notes in the accounts of Bishop Drtad Balian, and information obtained from the press, I have corrected them to the best of my ability.”

Student at Surp Garabed Monastery. Date and Name Unknown. Collection of M. Sarajian. Courtesy ProjectSAVE.

Students and Teachers of Surp Garabed School, 1898

Those individuals shown according to Alboyadjian (1937) are: 1. Bishop Drtad Balian 2. Myusi Danje 3. Daniel Nshanian 4. Nerses Zakarian 5. Haroutioun Nshanian 6. Haroutioun Sdepanian 7. Sdepan Kharian 8. Mgrditch Inayetian 9 & 10. Hovhaness and Krikor, the Garabedian brothers (stewards) 11 & 12. The Gyurunlian brothers 13 & 14. Sarkis and Hovhaness Bailikian (Boghosian) 15. Kalousd Garabedian 16. Haroutioun Damlamayan 19. Vahan Poladian 20. ? 21. Sarkis Khorasanjian 22 & 25. Kh. and V. Khachardian brothers 23 & 28. The Pamboukjian brothers 24. Garabed Tashjian 26. Garabed (Sinan) Sinanian 27. Garabed Tenekenian 28. ? 29. Hagop Matosian 30. ? (Mgrditch Inayetian’s cousin) 32. ? 33. Aram Seghbosian 34. Garabed Msrlian 35. Hagop Beylerian 36. Deacon Garabed Everegtsi 37. Mamas Zartarian 38. Deacon Haroutioun Everegtsi 39. Bedros Khachigian 40. Sarkis Hinaliyan 41. Yervant Kazazian 42, 45, 46, 51, & 52. ? 43. Haroutioun Keoleyan 44. Yeghia Srvazlian 47. Haroutioun Kasarnian 48. Damlamayan 49. Garabed Inneyan 50. Haroutioun Srvazlian

1892 - 1893

Vahan Garabed S. Kiurkjian, from Nirze

Hmayag Meldon A. Oughourlian, from Evereg

Karekin Mardiros Nahabedian, from Evereg

Nerses Zakaria D. Sdepanian, from Nirze

Khoren Garabed M. Keolian, from Talas

Mihran Y. Yenovkian

1893 - 1894

Parsegh K. Terzian, from Gesaria (later emigrated to America)

Israel Kh. Arslanian, from Moonjoosoon (later, an architect in Buenos Aires)

1894 - 1895

Kaspar B. Kasparian, from Talas (later, a trader)

Levon K. Malkhasian, from Gesaria

Smpad Ohan G. Ohanian, from Gesaria (later, a certified mechanic in France)

Mgrdich H. Keheian, from Gesaria (trader)

Aram A Saghrian, from Gesaria (died early)

Haig Jamouzian, from Gesaria (trader in Constantinople)

Vahan H. Ohanian, from Gesaria (trader in Gesaria)

Per Alboyajian, H. Oughourlian and G. Aprahamian also had the following names from this class:

G. Ohanian

Hohannes Kouyoumjian

Dikran G. Ghazerian

Bedros Gnkababian

Dikran Manougian

1895 - 1896

Garabed D. P. Elibeoyikian, from Gesaria

Mikael H. Yemenjian, from Gesaria (later, in America)

Garabed V. Berberian from Bünyan-i Hamid (trader in his hometown)

Mgrditch D. Inayetian from Germir (teacher)

Sarkis H. Arzoumanian, from Gemereg (teacher)

Sarkis N. Toshigian, from Gesaria (teacher)

Garabed S. Sezposian, from Talas (trader in Adana)

Hagop Tabibian, from Germir (died early)

Siragan N. Khoubeserian, from Talas (trader in Izmir)

Apel P. Gulbenkian (doctor), from Talas

Haroutiun M. Kzaprahamian, from Kyuchyukeo (later in Engyuru)

1899 - 1900

Mamas H. Zarkarian, from Fenes (later, Father Drtad)

Garabed K. Miaserian (doctor), from Efkere

1900 - 1901

Mgrditchian Kechian (doctor), from Germir

Sdepan P. Tabibian (doctor), from Germir

Souren H. Nshanian (doctor), from Germir

Haig S. Seghposian, from Talas (first a teacher, then a trader in Adana)

Garabed Morlian, from Talas (died at a very young age)

Yervant H. Kazazian, from Gesaria (later, a trader in Alexandria)

Sarkis G. Hinklian, from Talas (a teacher in Talas after 1902)

Sahag M. Malkhasian, from Talas (later, a trader in Aksaria)

Nazareth B. Beylerian, from Gesaria (teacher)

Khachadour G. Lordigian, from Gesaria (later, a trader in Gesaria)

1901 - 1902

Nazareth Bedros M. Khachigian (or Beylerian), from Gesaria (later, a teacher at Gesaria’s Gyumshian College)

Sdepan K. Hinklian, from Talas

Sinan G. Sinanian, from Efkere

Garabed M Hajinlian, from Gesaria

Hagop S. Hanjlnian, from Talas

Per Alboyajian: Bishop Drtad lists 10 graduates in two sets. Besides the first five who received first-division literary and science certificates, the following five are mentioned, who have received third-division certificates:

Garabed S. Bakalian (from Sebastia)

Yeghia S. Sivazlian (from Gesaria)

Sdepan T. Giragosian (from Gesaria)

Nazareth A. A. Arslanian (from Broun Kshla)

Garabed H. Keheian (from Gesaria)

1902 - 1903

Krikor H. Eorjian, from Hajin (teacher)

Nshanig Zelgeian, from Mersin (later, a trader in Mersin)

Sahag M. Malkhasian, from Talas

Sarkis B. Boghosian (Bdligian), from Gesaria (teacher, later in Paris)

Khachadour G. Lordigian, from Gesaria

Haroutiun G. Kasarjian, from Gesaria (later, a trader in Romani)

Garabed K. Tashjian from Gesaria (teacher at Gesaria’s St. Sarkis Church College in 1907)

Kevork H. Mndigian, from Gesaria (money-changer in Gesaria)

Krikor Der Aprahamian, from Giurin (returned to Giurin)

Vartavar D. Jzlian, from Giurin (returned to Giurin)

Khachadour H. Minoian, from Derende (returned to Derende)

Serovpe H. Ylanjian, from Giurin (later, teacher at the College of Germir)

1903 -1904

Armenag Khakhamian (doctor)

Hovhannes B. Boghosian

Armenag H. Kyahyaian

Nshan H. Mgrian

Vahan H. Poladian

Krikor N. Pamboukian

Yeghia S. Svazlian

1904 -1905

Vahan B. Isbetcherdzian

Setrak Harzovartian

Haroutiun Abadjian

Garabed Khatchigian

Mgrditch Tavtian

1905 - 1906

Garabed T. Aprahamian

Aram M. Sashagian

Garabed Koyoundjian

Hmayiag Karageozian

Mgrditch H. Childjian

Khoren Avakian

Sarkis Basmadjian

Haroutiun D. Daderian

Hampartzoum Delibashian

1906 - 1907

Kourken H. Toursakisian, from Hajin

Haroutiun Yaylaian

1907 - 1908

Vagharshag Pazoumian, from Talas

Garabed Toukhdarian

Yervant Yesayian, from Engyur

Aram H. Keheian

Sarkis Terzian, from Efkere

Aram Dadourian

Manuel Mardirosian, from Aleppo

Levon Der Hagop Ayvazian

Parsegh Der Hmayag Parseghian

Misag B. Balian

Bedros Tanielian, from Engyur

Haroutiun Reyisian, from Gasma

Garabed Koyounjian, from Samson

1908 - 1909

Kevork Hoviuian

Loutfig Yaghedjian

Serovpe Sahagian

Hovhaness Haroutiunian

1909 - 1910

Aram Karamanasian

Parsegh Minasian

Yervant Yesayan

Yesayi Keheian

Garbis Selian

Haroutiun Kechichian

Hovagim Ovayian

Per Alboyajian, the source of these names is Byzantium, No. 418. H. Oughourlian and G. Aprahamian only mention Yervant Yesaian from this list, and the following completely unknown names:

Ardashes Charklian

Kevork Kopoulian

Zakeos Ayvadian

Krikor Chakjian

Loutfig Chakmajian

Taniel Devletian

Hovhannes Doumanian

Hagop Khdrian

Krikor Koltoukian

Garabed Znnozian

Sarkis Jazmadarian

Adour Kabakian

Parsegh Khanlian, from Talas

Hovhannes Tellian

Aram Ouzounboghosian

1910 - 1911

Hmayian Hagopian

Hrand K. Nshanian

Garabed Avakian

Kevork Avakian (Garabed’s brother)

Ghazaros Hintlian

Diran Terzian

Armenag Dadreian

Levon Ayvazian

1911 - 1912

Piuzant H. Allahverdian

Mnag Tcherkezian

Tatoul Ihmayian

Hagop H. Nshanian

1912 - 1913

Onnig K. Miaserian

Manoug S. Avedian

Yesayi Sdepanian

Nazaret H. Salbashian

1913 - 1914

Antranig K. Nshanian

Arakel H. Giurinlian

Apkar H. Manougian

Kevork Tekeian

Kevork K. Berberian

Tavit Tadjirian

Mayag Dokt. Hagop Bey Dadrian

Levon Nishanian

Garabed (unknown surname)

Karnig Djrdjian

Boghos Boghosian

Hovhaness Torosian

Garabed Knadjian

Haig Balekdjian

Haroutiun Haleblian

Haroutiun Melegian

Reteos DerNersesian

Roupen DerHagopian

Simon L. Tekirian

Sarkis Yardemian

Onig P. Tabibian

1914 - 1915

Apraham Arabian

Armenag Melegian

Yeghia Melegian

Aram Kaplanian

Yeghia Bodigian

Levon Dedian

Khatchig Oknaian

Garabed Kalaydjian

Manoug Nshanian

Magar Tiutiundjian

Miridjan Simavonian

Hagop Tchergerian

Hagop Tanielian

Siragan M. Doukhterian

Sarkis Tatoulian

Smpad Tarpinian

Sarkis Yimidian

Sdepan Bahadrian

Vrtanes Seropian

Other Churches

In addition to the two chapels located within St. Garabed Monastery in Western Efkere, and in addition to Surp Stepanos Church, by the end of the 17th century there were at least two other churches located in Efkere, both on the eastern side of the village: Surp Sarkis, and Surp Kevork.

Surp Sarkis Church, and Surp Kevork Church are both mentioned by Simeon the Scribe in a manuscript from 1683, as is Surp Stepanos.

Surp Kevork Church and Surp Sarkis Church

Surp Kevork (St. George) Church was said to be a one minute walk to the northwest of Surp Stepanos. This was an extremely small chapel built into the rock. Once a year, on a day to celebrate Surp Kevork, the Divine Liturgy was celebrated here. As one left Surp Stepanos, and headed to the right, a door leading into this small chapel was said to exist near the top of the steps that led to the valley below. Alboyajian states that this was “like a small cabin with cells…There were four wooden crucifixes there, three paintings, and a small table…Every week, men and women would go there on pilgrimages.” This chapel was mentioned in an almanac from 1718, and in an interview that I conducted with a former resident, this chapel was noted to still exist in the early 1920’s, although it was no longer in use. Any further information, or photographs, would be greatly appreciated.

There is a structure standing in Efkere which may be the remains of Surp Kevork Church. Approximately 20 meters to the northwest of Surp Stepanos, there is a building which has been described by current residents of the village as having once been a “chapel”, with some elderly Turkish residents interviewed in 2002 remembering that religious services were held by the Armenians in this building. This fits both the location provided by Alboyajian, and also that I have obtained from elderly Armenian natives of the village circa 2000. This building will need to be studied further.

Below, you will find pictures of the structure taken in June, 2023. The third photo, dating from prior to 1915, shows the same building, with a black circle around it.

Below are interior photographs of this building from September 2005, which suggest that this was indeed once a chapel.

St. Sarkis was another small chapel, possibly also built into the rock, southeast of Surp Stepanos. According to Alboyajian, there was “a small table, two paintings, and four wooden crucifixes.” Like Surp Kevork, it was also a chapel built into the stone. It was located on the southeastern side of Surp Stepanos.

Surp Elia

Alboyajian describes yet another small chapel, at the highest point in the village, named Surp Elia. Alboyajian described it in the following manner in his 1937 publication, “Hye Gessaria”:

[There is] a place of pilgrimage called St. Elia, which can be found in the village’s southwest, at the edge of a small plateau, overlooking the whole village. Surrounded by ordinary rocks, the rotting, small main four walls, standing two or three arm lengths tall, made of …stones, open from above…can be seen. The width of the chapel is around 3 arm lengths, and its length five arm lengths….Bearing the mark of antiquity and a sacred place, no inscriptions are seen there. There was only a small table bearing the name of St. Elia near the eastern wall….It was an accident practice of the Efkeretzis to visit the cottage and celebrate Mass, offering sacrifice there, with the participation of the villagers, of St. Elia’s Sunday. On the same day, men and women from surrounding villages would also be present. Whenever there was a drought they would go there, too, and celebrate Mass in the open air.

While the structure no longer exists, at least one middle aged resident currently living in the area clearly remembered a chest-high, small structure, and pointed out the foundation of this structure for this author in June, 2023. The dimensions correspond very well with those described above.

In the pictures below, the first picture shows the view of the village from the site of the chapel, and the subsequent picture shows what remains of the chapel foundation.

To summarize, the Christian religious institutions that we know existed in Efkere include:

Surp Garabed Vank, and its two chapels

Surp Stepanos Church

Surp Kevork Church

Surp Sarkis Church

St Merecherios

St. Theodore.

Surp Elia

An Armenian Uniate (Catholic) Church—name unkown.

Turkish Sites

In addition to the Armenian religious sites mentioned on other pages, it is important to remember that Efkere was a village in which Armenians and Turks co-existed for much of its existence.

This website, for the time being, concentrates primarily on the history of Efkere prior to 1915.

Exact population figures are impossible to obtain but, prior to 1915, it is estimated that the Turkish Muslim population of Efkere consisted of 50 families.

For now, we are left to wonder where the Muslims worshipped during these early years.

Fortunately, Turkish scholar Hüseyin Cömert has released an invaluable resource with his publication of Gesi Vadisi. Census records for the village, as well as tax records, are released in his book for the first time, and they allow us to understand more about the makeup of the village.

Cömert relates that, according to the census records from 1831, Muslims resided in three neighborhoods: Fountain (Çeşme), Upper, and Northern. He stats that there were, in 1831, 240 Muslims in Efkere, with 29 families residing in the northern neighborhood, 8 in the upper neighborhood, and 11 in the fountain neighborhood.

A review of the property tax records from 1872 reveals the presence of a mosque on Hamit Efendi Stret, known as the Imam Kasim Mosque (as well as the presence of an Imam Kasim School). A masjid (small mosque) was located on the same street, known as Abdi Aga Masjod.

A masjid also existed on Çarşı Street, as did another mosque (name uncertain).

I do not know what became of these four structures.

The photograph above, taken in May, 2002, has been described by local residents as an old mosque. I have no idea as to the origins of this structure, or any more details on it. It is located in Eastern Efkere, a two minute walk to the southwest of Surp Stepanos. Any further information would be greatly appreciated.

A June, 2023 discussion with a local resident revealed that he believed a mosque existed in an area just northeast of Surp Stepanos church for several centuries. More research will need to be carried out.

A Camii (mosque) does currently exist in the village. It is a relatively new structure, and is shown above photographed in June, 2023.